“…it appears that for a moment they might instead have gone on to perform loud music, sung songs about the system that stinks and simply trashed their guitars afterwards. Big kids who grow wild and want to do beautiful things – without realising what it was they were really doing.”

Peter Körte writing on BAADER in the Frankfurter Allgemeine on Sunday, 30.12.2001.

“…es sieht so aus als wäre es einen Moment lang offen gewesen, ob sie nicht doch laute Mu-sik machen, gegen das “Schweinesystem” singen und hinterher bloß ihre Gitarren zertrüm-mern würden. Große Kinder, die wild werden und schöne Dinge tun wollten – und nicht wussten, was sie dann wirklich taten.”

Peter Körte in der Frankfurter Allgemeinen Sonntagszeitung vom 30.12.2001 über BAADER.

Georg Diez for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung 17.02.2002:

The reaction to the film’s premiere in Berlin was that of outrage and confusion: because it left the audience in a void, while leading them into the unclear terrains of ambivalence. And if there’s one thing the Germans can’t stand, it’s indecision and a lack of Prussian precision in judgement. Yet, “Baader” has a clear message – if you want to see it, that is: it becomes clear towards the end and says that every generation must rewrite and make its own mark on history, that it wants to reflect itself in the testimonies and the images of former generations and that it wants to assure that each and every generation has to claim these images for themselves. Some retrospective politics, a cut through the memory of a generation…

Particularly the final scene begs the question of what it actually was, that Roth wanted to tell us with “Baader” – although it was not just the whole concept of his film, as a more or less blurred biographical sketch, but also many other distinct divergences from history, that indicated the direction that Roth had chosen for his film. One example is the midnight meeting on a highway between Horst Herold, head of the Federal Criminal Investigation Office (BKA), and Andreas Baader. The final image is a very German showdown: Herold’s character as the father, Baader as the son – and between them, the fascination with guilt. Roth takes away everything that had made the lives of these young West German criminals seem like one breathless shot out of a Godard film and stages Baader’s arrest like some choreographed memory: the concrete of the houses, the people at the windows, the spies on the balconies, the grey-green of the uniforms, the pointless shooting. A short essay about the memory of a country that was also the country of one’s own childhood: a German hero, a tired and unshaven urchin who steps out of the garage with a gun in his hand, blinks insecurely into the light and recognises the state power in front of him. Should he shoot or should he pull the gun on himself? Indecisevely he throws the gun away. Then suddenly, a glimpse of memory flits over his face – a memory that reaches far into the future, almost up until the present. And with some totally unhistorical casualness, Baader pulls two guns out of his waistband and fires at the policemen until they have peppered him with their bullets. An imaginery end: The final shoot-outs from the cinema of the 90-ies have become reality. The father holds his dead son, both are looking into the sky, a concrete sky from which some disinterested people had watched the scene earlier on: now none of these window-box-spectators are watching anymore. They are allone…

Christopher Roth uses the Baader myth for his own purposes – and the subjective element of his view is slightly irritating: because the Germans have learned that guilt is given out in equal portions, and that they won’t be at any disadvantage, if they shout “here” every time they are drawing attention to themselves. Guilt was their mask behind which they could hide their faces because they were afraid that an ugly grimace might still confront them and resemble the faces from sixty years ago. They enjoyed the morally added value that helped them into a clear position because it faded out any contradictions…

The Germans feel a certain discomfort with the idea of contradiction, and the political right doesn’t do much more than yell: ”this is tabu”, which makes life easy for them. The political left is more prone to getting caugt up within their own arguments. Christopher Roth shipped his film into the shallow waters of the ideological shores, where easy answers would be cheaply obtained and where the irritation is huge, when someone looks for a different way out of the swamp of thoughts and pictures – a way towards one’s own truth, a truth that may be closer to the present day than to the historical events that are represented. The one who searches for historical truth in ”Baader” is looking into the wrong direction…

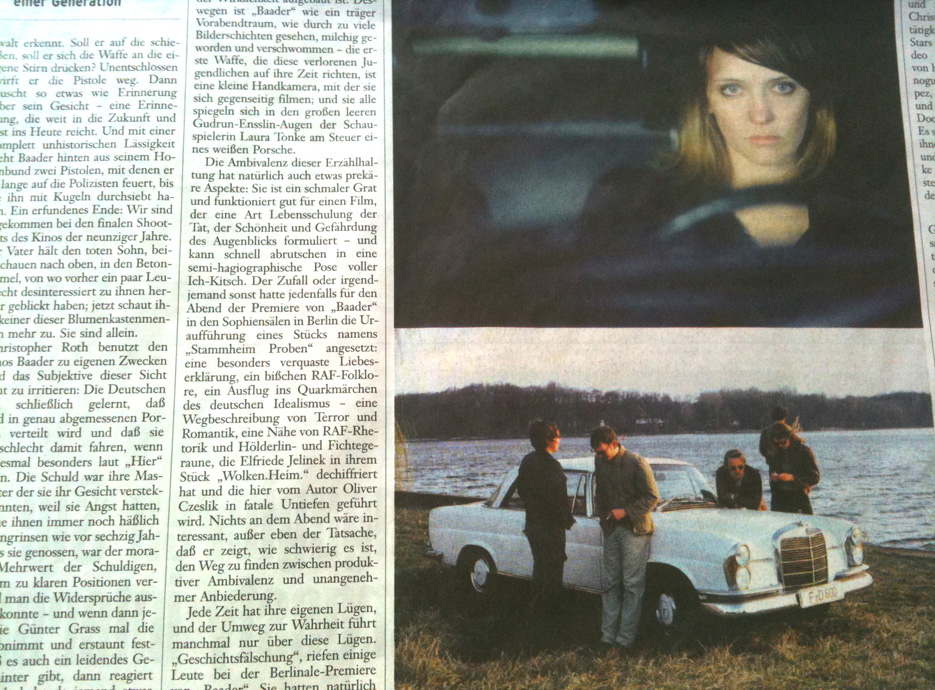

Evil is the price of freedom, as it says in the film. And because freedom, for this generation, sometimes felt like living in an overdimensional snowball, it is very tempting to summon the terror of the fathers’ generation, in order to destroy the pane between the present and reality in their name. Therefore ”Baader” is like a slow early-evening-dream, as if seen through too many picture-book-stories, it’s milky and blurred. -The first effective weapon that these lost youths are pointing at their time is a little handcamera, with which they are filming each other; and while actress Laura Tonke is sitting behind the wheel of a white Porsche, we can see a whole generation being reflected within her big Gudrun Ensslin eyes…

GEORG DIEZ in der Frankfurter Allgemeinen Sonntagszeitung 17.02.2002:

“Der Film sorgte bei der Premiere in Berlin für allerhand Verwirrung und lautstarke Empörung: weil er eine Leere hinterläßt, die ins unübersichtliche Terrain der Ambivalenz führt. Und wenn wir Deutschen etwas nicht ertragen können, dann ist das Unentschiedenheit und mangelnde Schneidigkeit im Urteil. Dabei hat “Baader”, wenn man sie denn sehen will, eine ganz klare Botschaft: Sie eröffnet sich vom Ende her und besagt, daß jede Generation neu die Ge-schichte für sich gewinnen muß, daß jede Generation sich in den Zeugnissen und Bildern der vorangegangenen spiegeln und vergewissern will, daß jede Generation diese Bilder für sich neu reklamieren muß. Ein Stück Erinnerungspolitik, ein Schnitt quer durch das Gedächtnis einer Generation…”

“Es war vor allem die Schlußszene, die die Frage aufwarf, was Christopher Roth mit “Baader” eigentlich erzählen wollte – obwohl nicht nur die ganze Anlage seines Films als eher verwischte biographische Skizze die von Roth eingeschlagene Richtung angezeigt hatte, son-dern auch andere deutliche Abweichungen von der überlieferten Geschichte, etwa ein nächtliches Treffen der Figur des RAF-Fahnders Horst Herold mit Andreas Baader auf einer Landstraße. Das Schlußbild nun ist ein sehr deutscher Showdown, der Vater Herold und der Sohn Baader und zwischen ihnen die Faszination der Schuld – Roth nimmt alles weg, was das Leben der kriminellen BRD-Jugend vorher wie eine einzige atemlose Einstellung Godards erscheinen ließ, und inszeniert die Festnahme von Baader wie eine choreographierte Erinne-rung: der Beton der Häuser, die Menschen an den Fenstern, die Spione auf den Balkonen, das Grüngrau der Uniformen, die sinnlosen Schüsse. Ein kurzer Essay über die Erinnerung an ein Land, das auch das Land der eigenen Kindheit war: ein bundesdeutscher Held, ein müder, unrasierter Bengel, der mit seiner Pistole aus der Garage tritt, unsicher ins Licht blinzelt und vor sich die Staatsgewalt erkennt. Soll er auf die schießen, soll er sich die Waffe an die eigene Stirn drücken? Unentschlossen wirft er die Pistole weg. Dann huscht so etwas wie Erinnerung über sein Gesicht – eine Erinnerung, die weit in die Zukunft und fast ins Heute reicht. Und mit einer komplett unhistorischen Lässigkeit zieht Baader hinten aus seinem Ho-senbund zwei Pistolen, mit denen er so lange auf die Polizisten feuert, bis die ihn mit Kugeln durchsiebt haben. Ein erfundenes Ende: Wir sind angekommen bei den finalen Shoot-Outs des Kinos der neunziger Jahre. Der Vater hält den toten Sohn, beide schauen nach oben, in den Betonhimmel, von wo vorher ein paar Leute recht desinteressiert zu ihnen herunter ge-blickt haben; jetzt schaut ihnen keiner dieser Blumenkastenmenschen mehr zu. Sie sind allein…”

“Christopher Roth benutzt den Mythos Baader zu eigenen Zwecken – und das Subjektive dieser Sicht scheint zu irritieren: Die Deutschen haben schließlich gelernt, daß Schuld in genau abgemessenen Portionen verteilt wird und daß sie nicht schlecht damit fahren, wenn sie jedesmal besonders laut “Hier” schreien. Die Schuld war ihre Maske, hinter der sie ihr Gesicht verstecken konnten, weil sie Angst hatten, es könne ihnen immer noch häßlich entgegengrinsen wie vor sechzig Jahren. Was sie genossen, war der moralische Mehrwert der Schuldigen, der einem zu klaren Positionen verhalf, weil man die Widersprüche ausblenden konnte…”

“Die Scheu vor den Widersprüchen ist dabei etwas sehr Deutsches, wobei sich die Rechte leichter tut, die nur “Tabu” ruft und fein raus ist. Die Linke ist anfälliger dafür, sich in Argu-menten zu verwickeln. Christopher Roth hat seinen Film in jenes Flachwasser der ideologischen Ufer geschifft, wo einfache Antworten billig zu haben wären und die Irritation groß ist, wenn jemand einen anderen Weg durch den Sumpf der Gedanken und Bilder sucht – einen Weg hin zu einer eigenen Wahrheit, die vielleicht mehr mit heute zu tun hat als mit dem, was war.

Wer bei “Baader” nach der historischen Wahrheit von damals fragt, schaut in die falsche Richtung…”

“Das Böse sei der Preis der Freiheit, heißt es einmal in dem Film, und weil sich die Freiheit für diese Generation manchmal so anfühlte, als lebe man wie in einer überdimensionierten Schneekugel, ist der Reiz groß, den Terror der Vätergeneration herbeizuzitieren, um stellver-tretend die Scheibe zu zertrümmern, die zwischen der Gegenwart und der Wirklichkeit aufgebaut ist. Deswegen ist “Baader” wie ein träger Vorabendtraum, wie durch zu viele Bilder-schichten gesehen, milchig geworden und verschwommen – die erste Waffe, die diese verlorenen Jugendlichen auf ihre Zeit richten, ist eine kleine Handkamera, mit der sie sich gegen-seitig filmen; und sie alle spiegeln sich in den großen leeren Gudrun-Ensslin-Augen der Schauspielerin Laura Tonke am Steuer eines weißen Porsche…”