Fri., Mar. 15, 2002 by EDDIE COCKRELL

It’s perhaps fitting that “Baader,” Christopher Roth’s sure-to-be-controversial biopic about ’70s West German celebrity terrorist Andreas Baader and his rise from small-time car thief to leader of the Marxist revolutionary Red Army Faction, uses only his surname in the title. Just as “Baader” is only part of his full name, pic can’t provide a complete, incisive profile of the man. However, terrific period verisimilitude, and the kind of wild and woolly visual approach favored by Oliver Stone in his so-called biopics, should result in strong local biz and subsequent attention wherever German society is a subject of interest or antiheroes sell tickets.

The film raises more questions than it answers about what really happened during West Germany’s “Decade of Terror” from 1968 to 1977, when the Baader-Meinhof Gang shot and bombed its way into local folklore as a kind of leftist Bonnie & Clyde. Just as it would be ill advised to use “JFK” as a teaching tool, “Baader” plays fast and loose with the facts. It should be viewed strictly as stylish, shallow entertainment.

Pic opens in 1972, as a chance traffic stop in Cologne spells the beginning of the end of the four-year crusade by Baader (Frank Giering) to stamp out capitalism and return to a socialist-based society. Time then shifts back to 1967 to lay the groundwork for his improbable rise to revolutionary theorist.

Along with g.f. Gudrun Ensslin (Laura Tonke), long considered the true co-leader of the gang, he firebombs a Frankfurt department store and flees to Paris after six months in prison. Returning to Germany and jail, he’s sprung by famous journalist-turned-social activist Ulrike Meinhof — thus minting the gang’s name and its growing reputation.

The brightest and funniest sequence finds them training at a terrorist camp in Jordan. Exasperated with Baader’s insistence that the gang be able to sleep together and sunbathe in the nude, the Palestinian leaders throw them out.

The height of the collective’s violent activity was in the period from summer ’70 to their capture in mid-’72. Dotted with date and place titles, pic breathlessly recounts the escalation of their activities to audacious bombings in newspaper buildings, American military bases and German police stations (the dead include four U.S. servicemen).

Stepping in with his own agenda is Nuremberg police chief Kurt Krone (Vadim Glowna). Pic’s most provocative scene finds Baader and Krone actually meeting along a deserted stretch of nighttime roadway. “Everyone does what he does best,” says the top cop. But “if you hadn’t killed anyone you might have achieved your goals.”

Relaxing the grip on facts may serve to heighten the drama, but that doesn’t explain the film’s jaw-dropping climax in which Baader is gunned down in a Butch-and-Sundance hail of police bullets. In fact, Baader, along with Ensslin and Jan-Carl Raspe, was either killed or committed suicide (the truth has never emerged) on Oct. 18, 1977, at Stammheim prison, where his various trials were dragging ever onwards.

Even at his most swaggering, Giering brings a sense of haunted turmoil to Baader, embracing Baader’s apparently rampant contradictions while at times looking strikingly like actor Kiefer Sutherland. Glowna’s world-weary slyness is a fine counterbalance, and the rest of the cast succeeds in underscoring not only the rather refreshing passion of the movement but also the naive youth of its members.

Tech credits are meticulous, with Roth’s blocking of actors and the slightly faded images of co-lensers Jutta Pohlmann and Bella Halben creating strong echoes of the period’s cinema. A much more accurate recounting of events can be found in Reinhard Hauff’s 1986 German drama “Stammheim.”

![]()

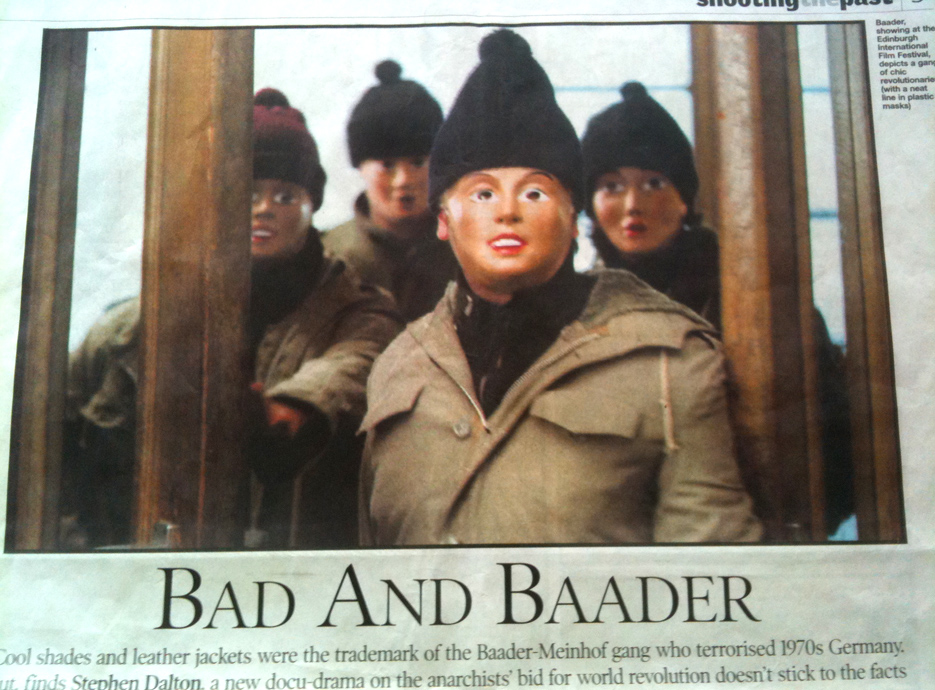

Bad And Baader

Cool shades and leather jackets were the trademark of the Baader-Meinhof gang who terrorised 1970s Germany. But, finds Stephen Dalton, a new docu-drama on the anarchists’ bid for world revolution doesn’t stick to the facts

They were the revolutionary pin-ups of 1970s Germany, cheered on by artists and intellectuals alike. Even after their bombs and bullets killed innocent civilians, the Baader-Meinhof gang were defended in court by many of the future Blairite moderates who now run Europe. These were violent times.

The 1960s utopian dream ended with the counter-culture up in arms, Vietnam still raging and Western youth out on the streets. In America, the Black Panthers and the Weathermen targeted the state as their enemy. In Italy, it was the Red Brigade. In Britain, the Angry Brigade. But it was Andreas Baader and his sharply dressed student guerrillas, trained by the PLO in urban warfare, who struck terror into the hearts of the affluent German suburbs where many of them had been raised.

Film director Christopher Roth wrestles with this potent mix of myth, mayhem and Marxist rhetoric in his controversial debut feature, Baader, which premieres at the Edinburgh International Film Festival this Friday. The Red Army Faction, as the Baader-Meinhof gang officially called themselves, had been proto-punk icons in Roth’s youth. ‘In Germany you grow up with these people,’ the dapper young director explains. ‘I always remember their posters, or you might have seen it on television. As a kid you would play, like Baader, against the police.’

Roth’s beautifully crafted docu-drama has yet to open in Germany, but it has already helped fuel a highly sensitive national debate about a controversial decade. Only a handful of films have dug up these skeletons before, none of them with the detail and reckless fascination of Baader. Volker Schlšndorff and Margarethe von Trotta’s 1975 feature The Lost Honour Of Katherina Blum attacked anti- terrorist hysteria even while the Red Army Faction were still in court. Then Reinhard Hauff’s sober reconstruction of the Baader-Meinhof trial, Stammheim, caused jury walk-outs after winning the Golden Bear at the 1986 Berlin Film Festival. In 1999, a far more ambivalent Schlšndorff returned to the subject of leftist radicals on the run in The Legend Of Rita.

But Baader is more personal than political, exploring the forbidden allure of gun-toting guerrillas who improvised their anarchist revolution on the run. ‘That’s very important,’ nods Roth. ‘If you make a movie where you say, ‘This is a very left wing or a very right wing movie’, it doesn’t make sense. I mean, why should I say this was good, this was bad? People should think themselves about what was good and what was bad.’

As played with a comically po-faced swagger by puppy-faced Frank Giering, Baader stamped his charismatic personality cult on the fringes of Germany’s radical underground. He was Charles Manson one minute, Che Guevara the next. ‘I first wanted to make a movie about another woman in the Baader-Meinhof gang,’ says Roth, ‘but then I found out that Baader is the most ambivalent figure in the whole lot. He’s a total asshole and on the other hand sometimes very generous and a great mind, but it switches all the time.’

As Roth explains, when revolution was fermenting in late-1960s Berlin at violent street demonstrations and hippie communes, Baader was a minor criminal in Munich with no clear polecat sympathies. ‘But then he came to Berlin and was kind of this dandy car thief, he could deal with girls and everything, and came in this group of students who were kind of too shy to talk to girls. They were very impressed by this guy who had a leather jacket and sunglasses. And in five years he changed to a really theoretical and revolutionary mind, and the students changed to criminals.’

In his mirror shades and leather jackets, Baader was a seductive figure to Ulrike Meinhof, the radical journalist who became his politcial muse, as well as gang member Gudrun Ennslin, who became his lover. The Red Army Faction’s image as romantic outlaws owed at least as much to Bonnie and Clyde as it did to Marx and Lenin.

‘They were kind of shooting a movie,’ argues Roth. ‘On one hand, when you got close to the group of terrorists, you were left-wing anyway, you knew Marx and Lenin, so Baader wasn’t in the position to have to explain all these things. He just gave them a car and a gun and said: you’re in a gangster movie, and now it’s getting serious.’

While it may seem trivial to present the Red Army Faction as radical-chic fashion models, as the Baader film does, in reality their keen sense of style was key to their subversive methods. As Roth learnt by meeting former terrorists and policemen, Baader encouraged new recruits to dress in chic gear and steal flashy BMWs, thus blending in with Germany’s young professional class rather than inviting police interest with scruffy hippie apparel.

‘I learnt quite a lot from one of the police guys,’ says Roth. ‘Little stories like how Baader went out in tennis clothes to check out cars, with tennis racquets and everything. And one former terrorist told me he was living for one year as a Lufthansa captain out of Frankfurt.’

As the gang’s exploits became more extreme and the manhunt to trap them escalated, Baader rarely compromised his vanity. Even at a terrorist training camp in Jordan, he refused to swap his red silk trousers for camouflage. When he was arrested after a police shoot-out in Frankfurt on June 1, 1972, Baader was still playing his movie bad-guy role in designer sunglasses. A distraught Gudrun Ennslin was caught a week later at a chic boutique after the bulge of her gun holster gave her away.

‘She was trying on a blue leather jacket in one of the most expensive stores in Hamburg,’ laughs Roth. ‘She was on the run and she went to buy a leather jacket! So yeah, it was a big thing to them.’

Roth’s movie fakes and fudges a few details, mainly for dramatic coherence. The anti- terrorist police chief Krone (Vladim Glowne), for instance, is a fictional amalgamation. But only in the presentation of Baader’s arrest does Roth move into the realm of fantasy, fabricating a heroic movie death for his anti-hero in a Butch Cassidy-style shoot-out. In reality, Baader was wounded in the leg, then spent five years behind bars before taking his own life in 1977.

Although sympathisers suspected a sinister police conspiracy at the time, most experts now agree there was a suicide pact between the core RAF members. But why did Roth, in a striking departure form the docu-realist tone of most of his film, rewrite history so flagrantly with this dramatic act of martyrdom? ‘We wanted to make clear that it’s a fiction film,’ he shrugs. ‘It’s really so over the top, so big, so emotional, that it’s so clear that this is a film. If you deal with this fascination with the first generation of terrorists I think you have to fictionalise because you have to deal with this emotional thing, and you can only deal with it if you fictionalise.’

Roth believes Baader will sidestep inevitable squabbles among ‘the ’68 people’ for rewriting their jealously guarded history. He has conducted a newspaper discussion in Germany with Daniel Cohn-Bendit, aka ‘Dany The Red’, the moderate European MEP who once led the rioting Parisian students of May 1968. Cohn-Bendit was positive about Baader, but many of Germany’s rulers will not relish having their radical youths dragged into the limelight. Foreign Minister Joskar Fischer, for example, had his street-fighting past exposed in a scandalous archive photo last year by Ulrike Meinhof’s daughter Bettina Rohl.

‘The minister for internal affairs in Germany was a lawyer for the Baader-Meinhof gang,’ smiles Roth, ‘and he has to deal with another lawyer who is from the neo-nazi party now, who was also close to the Baader- Meinhof gang. So we have all these people who are muddled up in the government, and it still pops up in these photos.’

Although the Red Army Faction suffered a fatal blow when their ‘first generation’ members died or went to jail, it is not widely known outside Germany that a second and third wave carried out sporadic kidnappings and bombings for two further decades. They officially disbanded in 1998 with a low-key press statement. In the past 30 years, of course, terrorism has lost its illicit allure among middle-class Marxists, and is now most closely identified with right-wing fanatics and religious fundamentalists. Roth agrees that Baader may be a hard sell in the wake of September 11, but he denies that he is glamourising those who spill innocent blood in the name of peace. ‘The film doesn’t suggest that it should be like that again,’ Roth says. ‘It just asks how could it have come that far, why was it like that, and what is the fascination? And this is where you have to ask yourself: why are you fascinated?’

Baader, 8pm, this Friday, Cameo, Edinburgh and August 18, 2.30pm, Filmhouse, Edinburgh

German cinema holds only 18% of its domestic market, other nationalities hold a little more, and American cinema takes all the rest. This explains the annual success of Berlinale, with the city audience for almost all programmed films, besides over 2000 accredited journalists. On this 52nd edition, good German productions stood out, including three on competition – “Heaven”, by Tom Tykwer, co-production with the USA (Jornal da Mostra 2/8/2002), “Halbe Trepe/ Grill Point”, by Andréas Dresen, and “Baader”, by Christopher Roth.

“Grill Point” despises all richness and resources available to German movies, from the sophisticated Arriflex cameras to the Babelsberg studios, and presents itself as a natural child of the Danish Dogma, holding a digital camera in hands and a nervous rebellion in mind and movements. Its characters could easily be taken for common people from small town. To be exact, at the German border with Poland, what can be seen as a pick on the German audience. Prejudice and resentment still persist on both sides of this border full of sad and tragic memories.

The previous film by Christopher Roth, “Night Shapes”, from 98, has already been a highlight at the São Paulo IFF. “Grill Point” is the name of a modest pub where two middle age couples delight the audience with their crisis. The pub owner’s best friend gets involved with his wife. Existential chaos is instituted and turns into tragicomedy. But without falling for easy comedy. Social critic is kept all along the film and gets close to the style of the British Ken Loach. That is, social conscience with an ethylic flavor and a lot of domestic intimacy.

“Baader” reconstitutes the 60’s when, in 67, Andreas Baader, a trivial car robber, turned into a historical myth and revolutionary martyr of extreme left wing. The theme is one of German politics taboos. Every time there is a film about the clandestine group that terrified West Germany in the 70’s, always launched at the Berlin Festival, polemic is instituted. This must be why Roth gives the film a documentary treatment, without taking sides or romanticizing the actions of the movement. Fact is that the impressions left are the political innocence of the movement known as RAF – Red Army Faction, what also irritates the ones that still defend the group’s validity and unconformity ideas. A complicated theme that results in an electrifying film.

(18/02/2002) Jornal da Mostra nº35

Leon Cakoff, de Berlim para o Jornal da Mostr

August 01, 2002

Terror of their ways

by Stephen Dalton

Cinema has always had a love affair with terrorists but a film about the notorious Baader- Meinhof gang is opening old wounds

This is hardly the most sensitive time to make a film depicting real-life terrorist killers as stylish young martyrs. But German director Christopher Roth’s chic low-budget retro-thriller Baader, which makes its UK debut at the Edinburgh Film Festival on August 16, poses some unsettling questions about society’s enduring fascination with radical outlaws, especially outlaws who dress like rock stars and drive BMWs.

Baader is the first film to tackle head-on the controversial story of Germany’s Red Army Faction, more commonly called the Baader-Meinhof gang. This underground army of former student radicals terrorised Western Europe in the early Seventies, killing police and army officers in the name of ending the Vietnam War, bombing newspaper offices and department stores as a protest against the “Fascist” German state.

These gun-toting Marxist dandies were finally defeated in June 1972 after their charismatic leader Andreas Baader, a former car thief with a flair for macho self-promotion, was injured in a Munich shoot-out.

Like his co-revolutionaries Ulrike Meinhof, Gudrun Ennslin and Jan-Carl Raspe, Baader later died in prison, apparently in a sensational suicide pact. But Roth’s film kills him off in an heroic hail of bullets, brazenly fictionalising a painful chapter in Germany’s postwar history.

“We wanted to make clear in the end that it’s a fiction film,” explains Roth over coffee in Berlin. “It says this is not historical fact, it lets you ask what else is wrong with this movie? And the other facts that people thought they knew, maybe these facts are wrong as well. People are criticising it because it is a fiction film, but I always say that’s fine if it’s irritating you — what else can a movie do? It’s great if you’re irritated, you start thinking about it.”

Growing up during a turbulent period in Germany’s history, when 20 years of postwar guilt collided with the explosion in campus revolution, Roth developed an ambivalent fascination with the rock-star radicals of the Red Army Faction. But he is not the first film-maker to flirt with terrorist chic.

“Terrorists are sexy,” insists director John Waters, whose most recent film, Cecil B. DeMented (2000), featured a radical underground gang of guerrilla film-makers. “Or they used to be. They’re right-wing now, and they have bad fashions. There’s only so much you can do with camouflage.”

For all his arch irony, Waters hits the nail on the head here. His “favourite terrorists” were the Sixties anarcho-pranksters the Weathermen, while former “urban guerrilla” Patty Hearst has even featured in his films — Hearst herself was also immortalised by Natasha Richardson in Paul Schrader’s crafted 1988 biopic. But such iconic outlaws belong to a more innocent age of Utopian left-wing idealism and Che Guevara posters on every student wall. Romantic notions of terrorist chic seem appallingly redundant in an era of teenage suicide bombers and religious fundamentalists flying airliners into skyscrapers.

Mainstream cinema has never had much time for serious debate about terrorism and its causes. Even at the peak of counter-culture radicalism, crime thrillers such as The Enforcer (1976) invariably depicted underground leftists as sick, violent draft-dodgers. Who Dares Wins (1982), in which deranged Marxist paramilitaries hold the US Ambassador to Britain hostage, was essentially a gung-go recruitment video for the SAS.

Even after radical chic subsided during the Thatcher-Reagan years, Hollywood continued to recruit nebulously defined revolutionaries as all-purpose villains. Alan Rickman’s Teutonic hostage-takers in Die Hard (1988), for example, were stripped of all ideology beyond greed. In the Eighties, even movie terrorists became Thatcherite entrepreneurs.

The only exception to this rule has been cinema’s long love affair with romanticised IRA gunmen, from James Mason’s poetic gang boss in Carol Reed’s classic film noir Odd Man Out (1947) to Brad Pitt’s vowel-mangling renegade in The Devil’s Own (1997).

Even so, the message of such films is invariably anti-violence and anti-terrorism. Perhaps the only mainstream film ever to offer a qualified endorsement of the IRA’s use of political violence is John Mackenzie’s classic 1980 gangster saga, The Long Good Friday, in which a cell of Republican assassins triumphs over organised crime and corporate corruption.

“I was very interested in this juxtaposition of politically committed terrorism in the form of the IRA which I had a sympathy with — although I would never condone a bomb — and capitalistic thuggery,” says Mackenzie. “Here was a capitalist land baron versus these revolutionaries or terrorists or whatever you want to call them.”

Baader is much more opaque in its sympathies, and therein lies its subversive intent. A handful of previous films have touched on Germany’s decade of terrorist chic, notably Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta’s The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (1975) and Reinhard Hauff’s Baader-Meinhof trial reconstruction Stammheim (1986), but docudrama detachment has been the watchword.

Although Roth consulted several genuine Red Army Faction veterans before making Baader, he is expecting flak when his Molotov cocktail of fact and fiction opens in Germany in October. “It is still very sensitive,” he nods, “because I think until nowadays the Left can’t deal with the whole topic that some people went underground and used violence.”

No wonder this is a sensitive subject, since many of those reformed radicals now run Germany. Not least Chancellor Schröder, himself a one-time Marxist whose past career as a lawyer involved representing Ulrike Meinhof’s close friend Host Mahler, a left-wing terrorist who later joined the far-right German Nationalist Party. Schröder’s Interior Minister, Otto Schily, also once defended Baader and Ensslin in court.

But most damning was the snapshot which resurfaced last year of Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer attacking a policeman at a violent 1973 demonstration. At the time, Fischer was already under pressure to resign after testifying at the trial of another ex-radical, Hans-Joachim Klein, for his part in a murderous raid on a 1975 Opec meeting in Vienna. In an intriguing twist, the source of the picture was Ulrike Meinhof’s daughter Bettina Röhl.

Baader has yet to secure a British distributor, but seems likely to provoke misunderstanding and hostility when it does. After September 11, can any film about terrorist chic hope to find a sympathetic audience? “It definitely gets another dimension,” Roth admits.

“Like when Baader says, ‘imagine a guy like a projectile who is moving towards death . . . ’ Then you suddenly shiver and think, oh my God, this has some similarity. But it was very small compared to what is happening now. It’s a different story.”